When Wounds Don’t Heal

by Shelly Blankman

I remember spending muggy summer afternoons on her porch, slurping fresh, fuzzy peaches, their sweet juices dripping down our chins. We’d giggle as we picked shredded napkins off our sticky fingers. Those were the times Mom laughed—when she could treasure the gentle breath of summer breezes wafting through the lilacs she so loved. We didn’t have many moments like that together—just she and I. The joys of life had been siphoned out of her long before I came along. She mostly lived in a cell of silent anger, and when her words spilled out, they were often like paper cuts—painful and deep.

Mom’s chilling childhood memories had cracked her own mirror of life. She had witnessed her mama day after day scrub the porch while neighbors sneered dirty Jew. Her mama could clean the porch but not wash off the stain of their laughter. She dared not shed tears or show fear. As a child, her mama had been the lone Holocaust survivor in a family of eight. She’d escaped to America knowing no one, learning early that without the armor of family, only silence could keep her safe. Hitler’s roaches had burrowed in every corner of the country. When my mom was told to stand in front of her class to show what a Jew nose looked like, she obeyed. Girls would tease her for having only two dresses, and she said nothing. Once she tried to collect money from a neighbor for the Red Cross. The neighbor snapped Just like a Jew and slammed the door in her face. Wound after wound after wound. And the deepest wound of all—the death of her baby brother because her mama couldn’t afford medical care to save him.

How do you fix a broken mirror? How do you pick up shards of glass without bleeding? In America, Mom and her brothers were raised in abject poverty and still considered rich Jews. Years and years of invisible tears. Shards still slicing open every wound of Mom’s childhood, suctioning the strength she needed to care for her family. How could she survive?

She found comfort in cats. She found love in cats. Toward the end of her life, her brain was scavenged by the scarab beetles of Alzheimer’s. She didn’t even know what a cat was. Her eyes were open, but empty until the day she died.

I never mourned her death. I mourn how she lived.

IMAGE: Lilac branch, digital art by Nadezhda Galimova.

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR: This was probably the most difficult poem I’ve ever written. My mother had a difficult life, and I didn’t realize until my adult years about the impact the Holocaust had on survivors and following generations. I wanted to show her struggles and strengths, and her history was very much a part of that. I wanted to share all that was missing in her life, because she deserved more than that. She didn’t have the voice to tell her story. But I do.

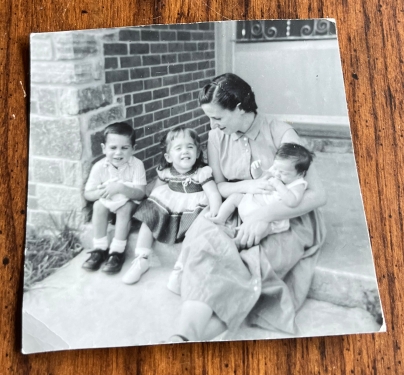

PHOTO: The author (second from left) with her mother and siblings in Baltimore, Maryland (1956).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Shelly Blankman lives in Columbia, Maryland, with her husband of 43 years. They have two sons, Richard and Joshua, who live in New York and Texas, respectively. They have filled their empty nest with four rescue cats and a dog. Richard and Joshua surprised Shelly with the publication of her first book of poetry, Pumpkinhead. Her poems have appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, Verse-Virtual, Muddy River Poetry Review, and Open Door Magazine, among other publications

Oh, Shelly, I am weeping!

How sad.

My dear Shelly, you have beautifully honored your mother, your family, your ancestors. Bravo.

Just honest, eloquent writing that comes from deep within the personal pain and compassion for self and others. For more of the same, I highly recommend Shelly’s book, “Pumpkinhead”.

I stared at the blank “leave a comment” screen for too long, trying to come up with words to describe how I’m left feeling from your heartbreaking poem. All I can muster is to thank you for bravely penning this impactful, emotive piece. God bless you.