Kintsugi

by Beth Copeland

Mother’s Japanese friends

send cards she forgets

to open—prints of blond

birds flying

over turquoise waves, pine branches

burdened with snow. Her mailbox,

stuffed with letters

and junk. I slice

into an envelope and pluck a handwritten

note from Kinko-san: I have not heard

from you. I am worried. You are so

old. Mother snorts, She’s

almost as old as I am!

and we laugh

at what’s lost

in translation. She forgets bills,

to brush her teeth or swallow

her thyroid pills and Lipitor

but remembers Kinko-san

from long ago. Should I write to say you’re

okay? I’ll do it

later, but she won’t. She stares

at a maple for hours when I’m

not here, her hair a corona

of uncombed

dandelion seeds. Should I

laugh or cry? Like a broken

bowl mended with molten

gold, she’s more

beautiful than before. I hold

her in the heart

of my heart

where she’s whole.

Originally published in the author’s collection, Blue Honey, recipient of the 2017 Dogfish Head Poetry Prize, The Broadkill River Press, 2017.

PHOTO: Teacup with gold streaks exhibiting Kintsugi repair (Vlad islavovich, photographer). Kintsugi celebrates breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise.

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR: I wrote “Kintsugi” when my mother was in an assisted living home because she had short-term memory loss. She would forget to check her mail, and one day we found a card from Kinko-san, a woman she knew when she and my father were serving as missionaries in Japan during the 1950s. She and Kinko-san had corresponded with each other for 50 years.

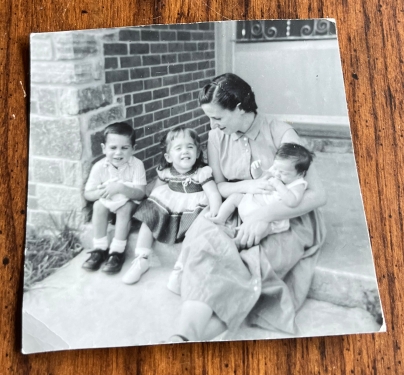

PHOTO: The author with her mother Louise, her older sister Joy, and Kinko-san and her family on the occasion of Kinko-san’s son’s first birthday.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Beth Copeland is the author of Selfie with Cherry (Glass Lyre Press, 2022); Blue Honey, 2017 Dogfish Head Poetry Prize winner; Transcendental Telemarketer (BlazeVOX, 2012); and Traveling through Glass, 1999 Bright Hill Press Poetry Book Award winner. Shibori Blue: Thirty-six Views of The Peak, a collection of her original photographs and poems, is forthcoming from Redhawk Press.