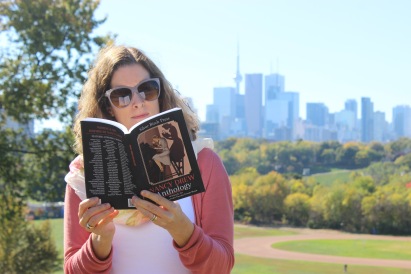

We asked the 97 contributors to the Nancy Drew Anthology (Silver Birch Press, October 2016) to send photos featuring the book in their home environments for a series we’re calling “Nancy Drew Around the World.” Author Lee Parpart provided this photo taken at Riverdale Park in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, with the CN Tower and the downtown Toronto skyline in the background. Lee contributed the prose piece “Nancy drew,” featured below, to the 212-page anthology.

Nancy drew

Whenever things got slow around River Heights, or when there were personnel changes over at the Stratemeyer Syndicate that upset her or made her feel less invested in her own development as a character, Nancy coped by drawing.

Her most fertile period as an artist came in the gap between books 7 and 11. Mildred A. Wirt, aka the first Carolyn Keene, was on strike to protest the lowering of freelance rates at the syndicate during the Depression, and had been replaced by a male journalist, who wrote books 8, 9, and 10.

To distract herself from the loss of her preferred author, Nancy drew. In the couple of years that passed between The Clue in the Diary and The Clue of the Broken Locket, she completed at least a dozen self-portraits, crowding most of them onto a single large sheet of paper left behind by one of the Stratemeyer illustrators. For each drawing or set of drawings, she used a different method to capture some aspect of her appearance or some element of her character that she suspected might have been missed.

The first two sessions took the form of a mystic, Dada-style experiment in automatic writing, with Nancy wearing a blindfold and giving herself exactly one minute per portrait. Instead of drawing her own features, she sketched a rough outline of her body, then attempted, without being able to look at the lines, to fill the image with written notes.

The first one made her look like a polar bear and overflowed with adjectives handed down by various members of the team responsible for her creation: Peppy, Plucky, Curious, Kind.

The other attempt, which came out looking more like a real female silhouette, contained words and phrases not heard around the office, but whose meanings resonated with her as possible clues to her overpowering, lifelong need to identify and solve mysteries. Unflinching. Dogged. Determined. And a more shadowy phrase that was just coming into parlance in America at the time: anti-authoritarian.

In a bad experiment never to be repeated, Nancy drew one portrait of herself while driving her blue roadster through the center of River Heights. This was deeply out of character and almost had dire consequences when Nancy hopped a curb near the soda shop and came close to hitting a young couple in mid-kiss.

An equally frivolous, though much less risky, formal approach involved using vegetable-based watercolors to create a simple portrait of herself driving the roadster, then using treats to encourage Togo to lick the image until it took on a loose, indistinct quality that made her think of beaches and Toulouse-Lautrec.

In homage to both M.C. Escher and her main creator, Nancy once depicted herself as half a silhouette in the process of being drawn by the curved hand of Mildred Wirt. Nancy knew Mildred was a writer, not an artist, but she wanted to be sure to give the almost forgotten original author due credit for her own existence.

In one final drawing carried out shortly before Mildred was reinstated, Nancy used a magnifying glass to closely inspect the skin of her forearm, and devoted herself to reproducing exactly what she saw there. Good detecting was about learning how to look, and she wanted to test her skills at observation with an abstract visual puzzle. She focused intently on this task for several days, finally producing an intricately detailed, almost trompe-l’oeil, rendering of a one-inch patch of skin that included a network of criss-crossing lines not visible to the naked eye, punctuated by a small brown birthmark that she had known was there, but never bothered to explore. At the end of this intense period of struggle and reflection, she felt she knew herself better than at any other point in her story.

Nancy drew until she became tired of drawing. Mildred Wirt returned to the publishing house later that week, almost as though she was summoned back by the creative energies of her own creation. With Stratemeyer’s personnel problems solved, Nancy sat down next to her author and began to think about writing.

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR: “Nancy drew” isn’t exactly a short story. It’s closer to a piece of conceptual fiction, supported by elements of nonfiction. As some devoted fans of the Nancy Drew series will probably recognize, the references to the Stratemeyer Syndicate and Mildred Wirt’s job action in the early 1930s are based in fact.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Lee Parpart worked as an arts journalist and a media studies researcher before returning to her earliest passion, creative writing, in 2015. Her essays on Canadian, US, and Irish cinema have appeared in books and journals, and she has served as a film and visual arts columnist for two major dailies. Her poetry has appeared in numerous Silver Birch Press series, and she was named an Emerging Writer for East York in Open Book: Ontario’s 2016 What’s Your Story? competition, which highlighted the work of writers in four neighbourhoods across Toronto. Her short story, “Piano-Player’s Reach,” appeared in an anthology published by the Ontario Book Publishers Organization. To find out more about Lee’s work, please visit her website.

Find the Nancy Drew Anthology at Amazon.com.

Author photo by Ron Wadden.